My two cents on negative gearing is that it might not really matter. It’s what’s going on in the policy environment around negative gearing that counts.

The negative gearing debate has gone full tilt.

… again.

This is one of those issues that just doesn’t go away, and divides Australia up like the State of Origin.

But it feels a bit different this time doesn’t it? Maybe both sides are politics are looking into the budget hole left by collapsing commodity prices, and suddenly everything’s on the table.

Abbott has ruled it out, but Chris Bowen won’t.

Or maybe the public has woken up to the fact that cuts need to be made. Pain is inevitable. Now we’re just seeing some jostling about who shoulders the burden.

And ‘wealthy’ property investors are lining up to take a kicking again.

Now negative gearing is not part of my strategy, but I do get miffed to hear people label all property investors as wealthy fat cats living large like some sort of landed gentry while their tenants/serfs pay the bills.

Most property investor I know did not start out with a silver spoon in their mouth. (But then I do move in certain circles. My golf club membership lapsed a long time ago.)

And most property investors have achieved financial freedom and security through a lot of hard work and sacrifice. They’ve saved hard, taken risks, put time and energy into their strategy and skill set.

If they’re reaping the rewards of their labours now, all power to ‘em.

Anyway, negative gearing is all over the press, so I won’t go over everything that’s out there already. But there are a couple of things that I haven’t seen anyone talking about. That can be my two cents.

The first is about who gets the benefits of negative gearing. The answer to this seems to depend on how you cut it up.

If you just look at the numbers of people, then it seems that most people who negative gear are middle income earners.

But in a way, that doesn’t really tell you too much. Most people overall are middle income earners, so all that says is that the negative gearing distribution follows the income distribution.

It doesn’t tell you that negative gearing favours middle-income earners, but it doesn’t tell you that it disadvantages them either.

But then if you look at who gets the dollar value of negative gearing concessions, this seems weighted to higher income earners.

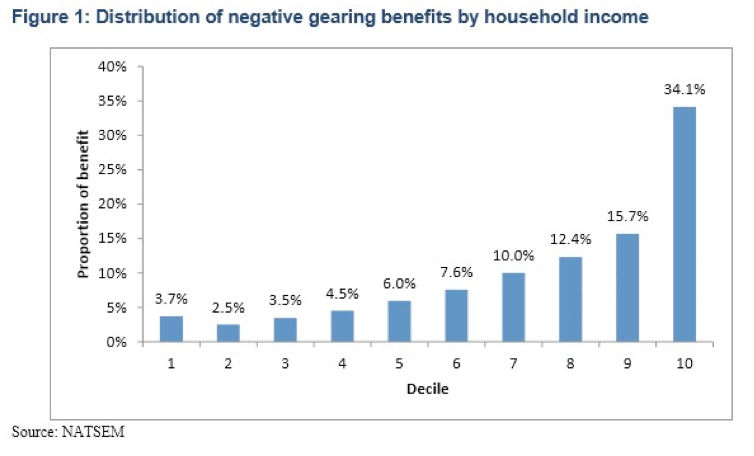

NATSEM modelling reported by The Australia Institute shows that over a third of negative gearing benefits flow to the top 10% of income earners.

The bottom half of Australian income earners get just 20% of the benefits.

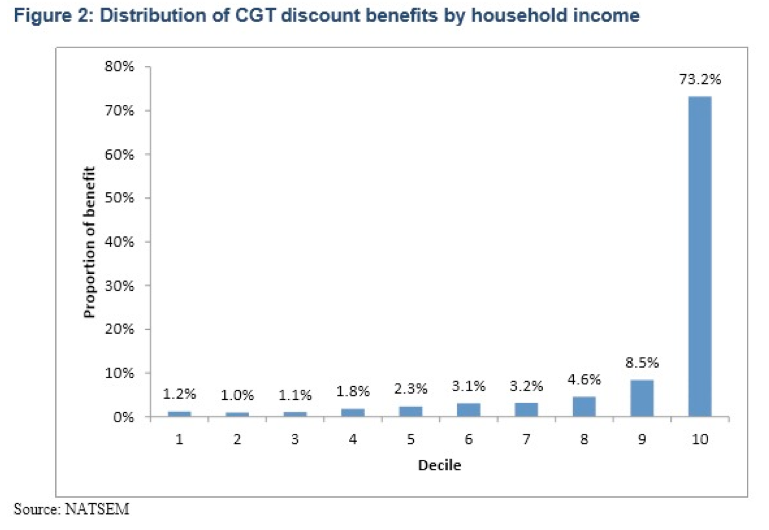

Looking at the capital gains tax concession (which is often the other side of the coin in a negative gearing strategy), it’s an even more dramatic picture

The top 10% of income earners get 73.2% of the benefits, while the bottom half get just less than 10%.

Pretty damning right?

But my response to this is kind of, “well, duh.”

Partly this just reflects where wealth is concentrated in Australia (it’s a lot less even than people think!)

It also reflects the fact that wealthy people tend to have significant property holdings in their portfolio. Property is a proven long run wealth creator, and the rich know this. And so any tax policy that engages with property is automatically going to be disproportionately engaging with the portfolios of the wealthy.

But it also reflects the fact that as you become wealthier, you have more and more options you have for optimising your tax. I imagine that if you look at any tax concession on offer, it will be disproportionately utilised by the wealthy – simply because they can.

So we need to unpack this. Maybe you don’t want negative gearing to be used as a tax break for the wealthy. I can understand that. But negative gearing might still have features you like.

Maybe it’s a way for younger or less wealthy folk to get in on the property ladder sooner, and start out on the road towards financial autonomy earlier. That could be a good thing.

And maybe you want to encourage investment in new housing. That’s also a worthwhile aim…

My point is that if the problem is with wealthy people using it to dodge tax, – fix that problem. Turfing negative gearing altogether isn’t the only option.

I’m sure it wouldn’t be hard to introduce a few tweaks that capped claimable losses, or limited it to certain segments or whatever.

The last thing I’d say is that one of the key criticisms of negative gearing is that it doesn’t do enough to increase housing supply (which was kinda the point). And it is true that something like 90% of investors purchase existing houses, not new ones.

That means that negative gearing puts pressure on prices, without contributing to supply.

Maybe that’s true, but I don’t think you can just look at negative gearing in isolation like that.

The question you really need to be asking is how easy is it to bring new supply to the market.

And as I’ve written about many times, Australia is a chronic underperformer at bringing new housing supply on line.

And that seems to be mostly to do with excessively strict planning and land-release policies.

Negative gearing could be an awesome way to encourage new supply to market – but only if our planning polices are pulling in the right direction. Right now that isn’t happening.

So if negative gearing isn’t working as well as it was supposed to, it might not be negative gearing’s fault. Maybe planning policy is the first port of call..?

Anyway, that’s my two cents.

What do people think?

Negative Gearing: Time to go or leave it alone?