On Tuesday, I showed you that young people are actually not smooshed avocado eating hipster whingers.

(Who would have thought?)

I showed you some amazing charts that prove just how much harder the property market is for young people these days. (If you missed it, Part 1 in this series is here.)

Before I can help you understand just what to do about it (which I’ll do tomorrow), we need to understand just how we got here.

Why are Australian house prices so crazy expensive?

In economics, everything’s a balance of demand and supply. It is true that we probably haven’t been building enough houses, and the government could be working on the planning system here.

However the real story for my money is five massive disruptions on the demand side of the ledger. These big five help us why you need to cough up a fortune to buy a house in Australia.

Credit is a lot easier to get than it used to be. When I first starting borrowing money, you had to get a haircut, put on a suit and grovel at your bank manager’s Italian leather shoes.

Now, you can do it all online, and you have mortgage brokers falling all over themselves to help you get the finance you need.

This is what financial sector deregulation has given us – easier access to credit, plus a more competitive financial sector, which has put downward pressure on mortgage rates.

Win.

At the same time, there was a structural break in official interest rates with the death of inflation. Pretty much around the world, central banks are more worried about deflation than inflation these days, and this has let them drop interest rates to record lows.

Mortgage rates have followed the train south, and we now have access to some of the cheapest money ever.

This super-abundance of credit means that an individual on a given income can now borrow a lot more than they used to, and this has lit a fire under house prices.

The interesting thing about this is that access to credit is a bit regressive. If you’re just starting out, with a casual job, not much deposit – then the banks don’t get too excited about you. You probably have to pay LMI.

However, if you’re like me, an investor with a large property portfolio, good income streams etc, then banks are falling over themselves to throw money at you (I have to take in an industrial vacuum cleaner in with me just to hoover it all up).

So, cheap credit helps us buy houses, but it helps some people more than others.

In 1999, the Howard Government decided to tax capital gains at half the rate applicable to other income. This turned negative-gearing into an effective strategy for deferring and permanently reducing your personal tax liabilities.

(For the full story on negative gearing, see this explosive report from property guru Jon Giaan.)

The incentives were in place, and people followed. (Hate the game, not the players.)

What happened was that we saw a surge of investors enter the market, and a lot of these newbies were using negative gearing.

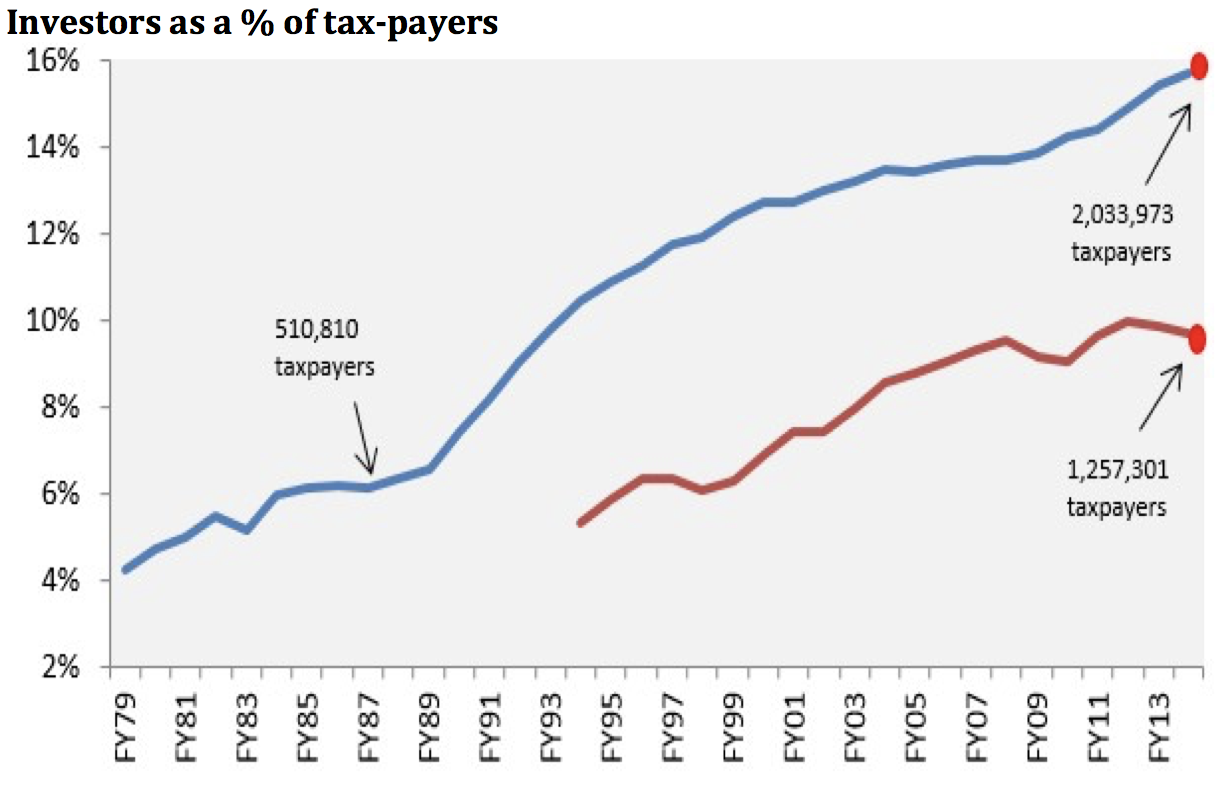

Investors as a % of tax-payers

By 2012, the number of negatively geared property investors outnumbered “normal” investors 2:1! Most accountants you talk to think that negative gearing is the normal way to invest in property.

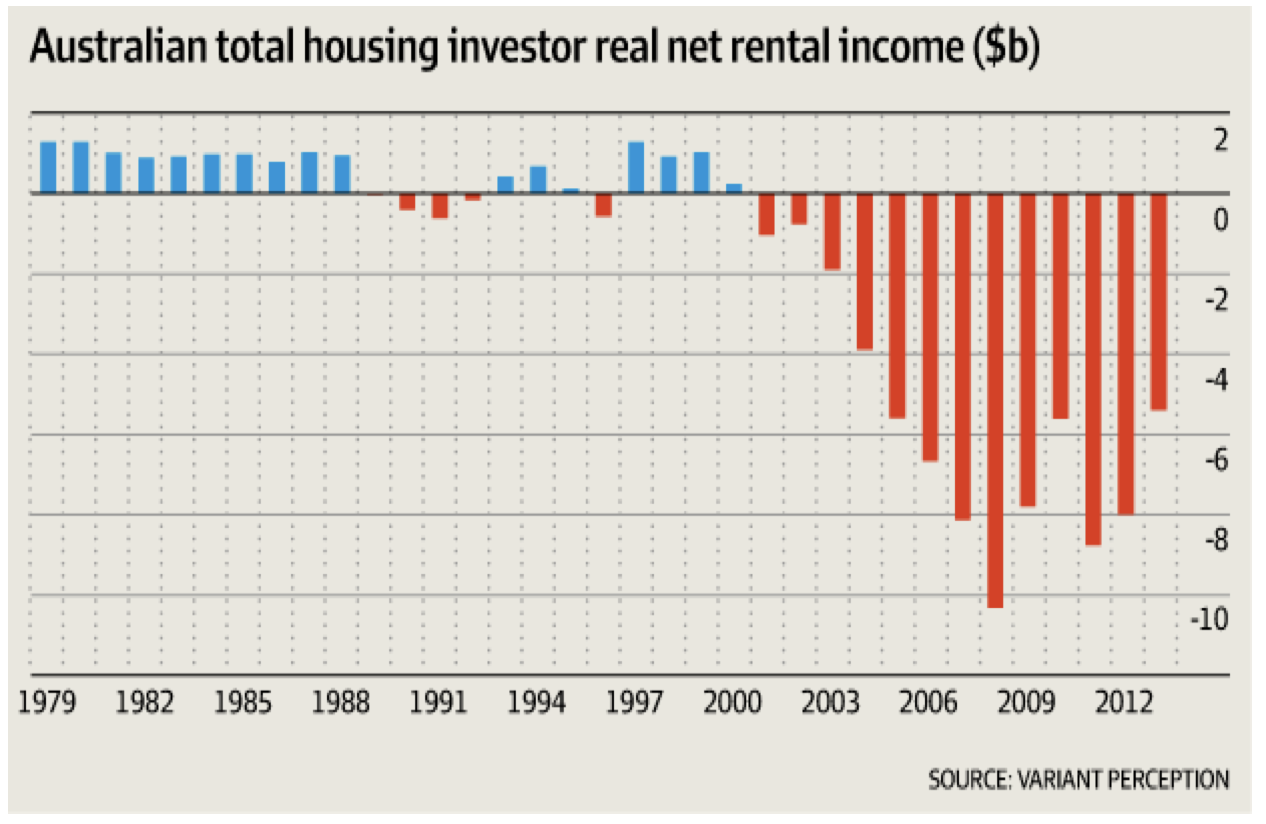

As a result, Australians collectively lost billions of dollars on their investment properties – almost $10bn just in 2008 alone!

But individuals were happy to lose this money because they’d make it back in deferred tax and capital gains.

What it did though was totally change the maths of property investing. For a property offering a given rent, investors would now be willing to pay more for it. Whatever extra interest costs they incurred would be sorted out by the negative gearing / CGT tango.

With a million extra investors in the market, all willing to pay more than the market was previously willing to pay, prices rose.

It might not have had such a big effect if investors were building new houses and adding to supply, but very few of them were.

By 2015, only 5% of investors were investing in new housing. The rest were bidding up the price of the existing housing stock.

Remember how I noted the structural breaks in a lot of series around 2000? This was exactly the time that the NG/CGT changes came in.

Coincidence much?

I don’t think so, Penny.

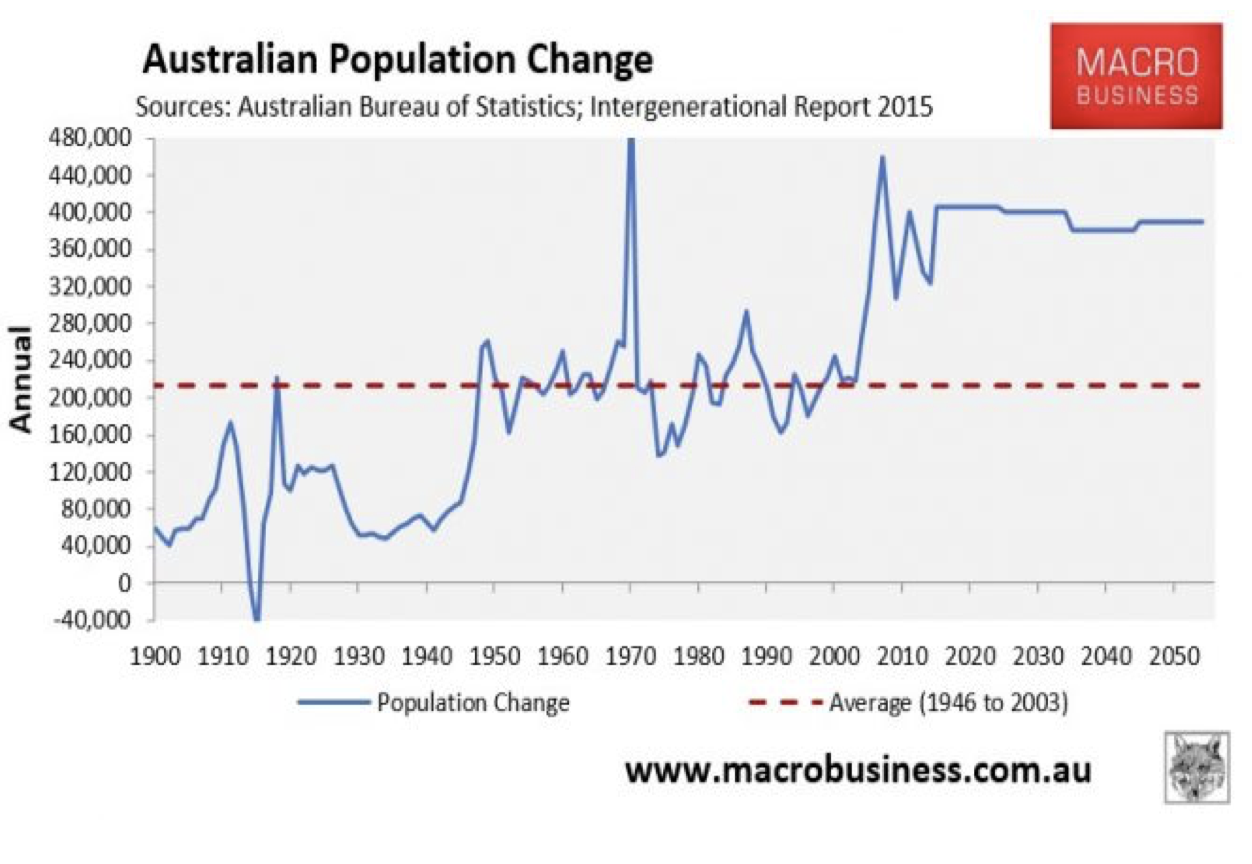

At the same time as these changes were going on, Australia also opened its doors to higher levels of immigration. Again, around 2000, immigration levels spiked and have since held at historically high levels. What’s more, they’re projected to remain at these super-charged levels into the foreseeable future.

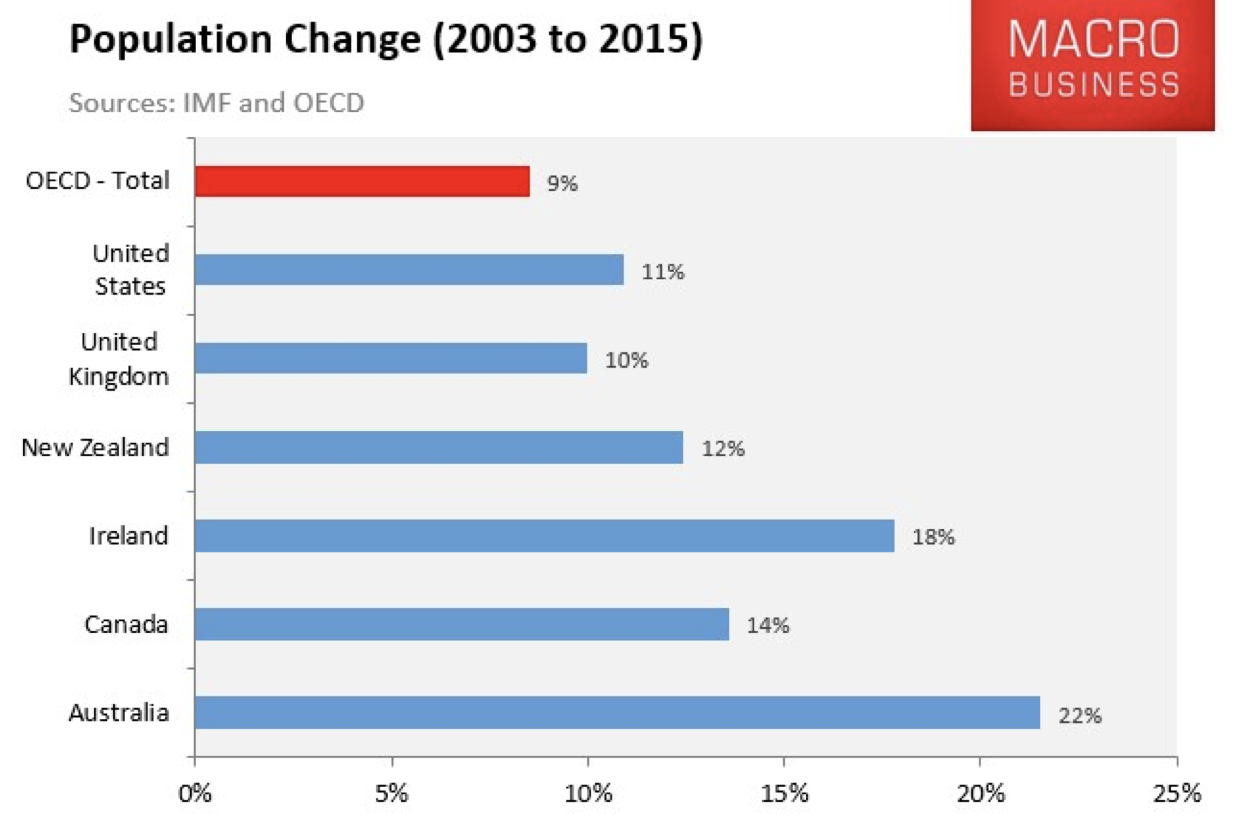

As a result, between 2003 and 2015, the Australian population had one of the fastest growth rates in the OECD. We grew twice as fast as America. This was partly due to improving birth rates, but it was mostly about immigration.

It’s not hard to guess what impact this has had. It is people that buy and need houses. If the number of people competing for houses goes up, prices will rise…

… and they did.

The other thing governments did in the first decade of the century was throw heaps of money at first home buyers.

First Home-Owner Grants have been around for a while, but for the first time, the means-testing was totally removed. They were available for everybody.

Even toddlers.

Effectively, the government pumped something north of $15bn into the market, and then they were surprised when prices rose.

Governments have now seen the error of their ways, and FHOGs are mostly smaller and restricted to new builds these days – though rules vary state to state.

The point is FHOGs don’t offer today’s buyers much except a legacy of higher prices.

Sucks to be you.

Foreign buyers have been big players in the market in recent years. They’ve been driving off-the-plan apartment purchases in the big cities, but they’ve also had a healthy appetite for existing houses.

Under long-standing rules, foreign residents aren’t allowed to buy existing property, but the enforcement of these rules has been pretty piss-weak.

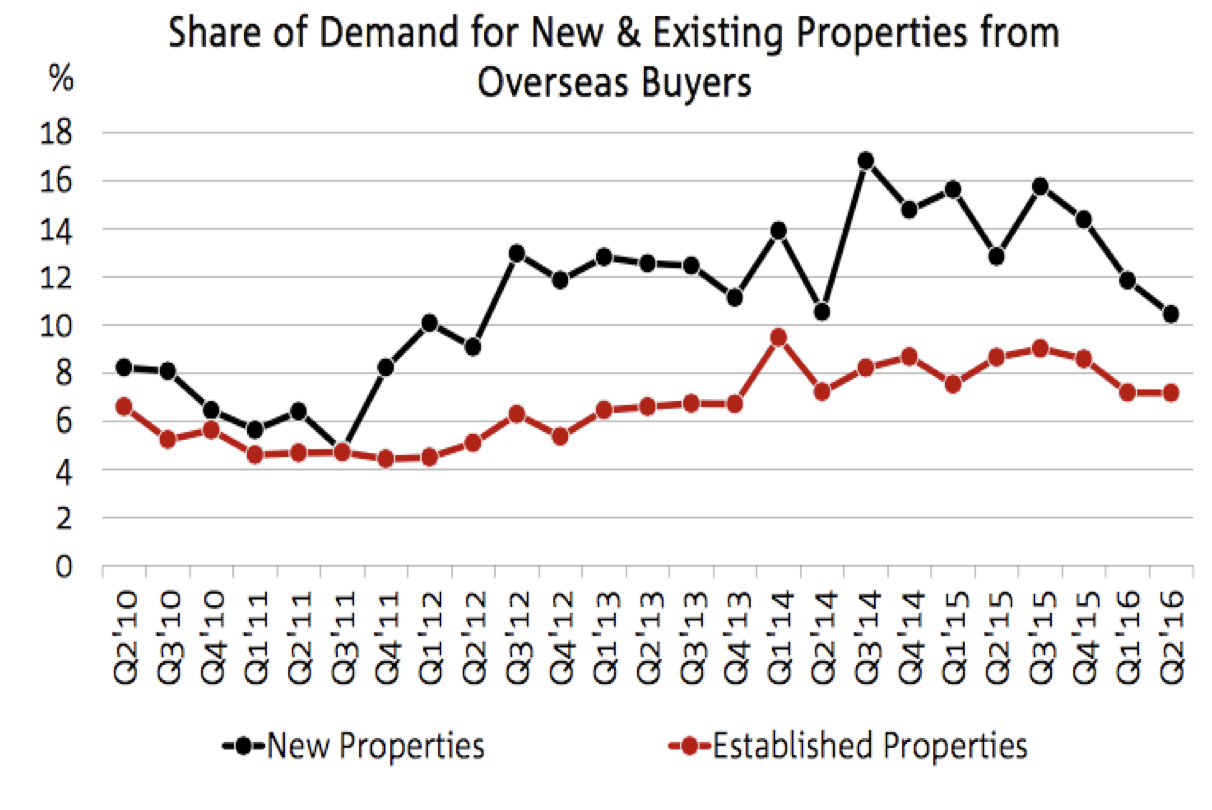

There’s no official data (part of the problem!), but survey work suggests that at the peak in 2014, foreign buyers accounted for 17% (almost one in five) new property purchases, and 10% of existing property sales.

We know very little about who these buyers are or where they come from, but we do know that many just pay with cash.

Cold, hard cash.

Can you compete with that?

These five disruptions created a perfect storm for property and price rises were inevitable. Once I saw the tsunami of cash headed our way, I made sure I was well in the way of it.

There was good money to be made for sophisticated property investors, but then there was also good money to be made for total hacks.

These five disruptions created what I call a dart-board market. That is, you could pin up a map of any capital city, throw a dart at it, and whatever property it landed on would be a winner.

As a result, a lot of hacks think they’re property geniuses and are more than happy to lecture any young people who’ll listen.

It also gave us these absurd urban myths, like all properties in all markets double every seven years, in all cultures throughout history and across all space-time.

However, these dart-board days are coming to an end. From where I sit, I still see plenty of opportunities in the market, but the dart-throwers will need to be careful.

I wish I had happier news to give you. I wish I could say that all of these factors are about to reverse, and soon $300,000 will buy you a large suburban house in the city.

But I’d be lying.

The market has evolved. Maybe it’s devolved. The point is it’s changed and there’s no going back.

The only question now is, what do we do about it?

Tune in tomorrow and I’ll lay-out a blue-print for affordability in Australia, and show you just what young people can, and are, doing.

There is hope.

x.

Dymphna